|

| According to this chart, I am Roman and I plan on applying for an Italian passport now. |

As some readers of this blog know, I am currently working on a book that has been about 10 years in the making--a discussion of race and ethnicity in Greco-Roman antiquity and some of its modern implications and complications (I talked about it with Elton Barker of

Classics Confidential in Jan.). The book is yet untitled (I am trusting the people at Johns Hopkins University Press who get paid to come up with cool titles to help me out). One of the primary points of this blog is to give me a space to work through my research in a less formal setting as I try to figure out just what it is that I want to say and, of course, just what I think is happening in the past.

This is also something that I am fortunate to be able to do with students as well since I get to teach my research and the kids these days are really good at helping me see things from different angles. And I am also fortunate in having this space where I can work on improving how I communicate my scholarship to wider audiences than what scholars normally aim at (i.e. the 6 people in the field who work on our specific areas).

Anyway, back in January, I tried working through some of the issues with talking about 'race' and 'ethnicity' in antiquity and how it is

historically contingent and what that means. As I work through writing the introduction to the book, I've given it some more thought. This is where I've gotten to (and it is likely not the final word). You'll see that I have a different approach than previous scholars who have discussed race in antiquity, though it won't be surprising to anyone who has studied contemporary race.

My question for today is ‘can we even talk about race and ethnicity in greco-roman antiquity?’ Obviously, enter any room and ask this and you will get numerous yeses and probably more nos. More importantly, there are likely in any room a dozen different definitions of race and ethnicity floating around and so when we speak of whether it exists in antiquity, we aren’t all really sure what we are considering.

RACE

Let’s start with ‘race’ since it has the longer, more complex history and because I really want to focus on it and just talk a little bit about ethnicity. And, because, ‘race’ as a concept has been around as long as the discipline of classics (way longer, in fact) and has been intertwined in its study and place in both the university and the popular imagination. And yet, what it has meant and how it has been applied as a concept has changed over time and its connections to classics erased or obscured.

Ways to talk about race in Antiquity

Option 1. Modern ‘somatic’ or 'epidermal' race: restoring color to the ancient world; valid--the history of the disciplines of ancient and medieval studies has been to exclude and erase people of color from the ancient Mediterranean.

Option 2. Race more as a technology that structures human interactions and embeds prejudices against racialized peoples into systems of oppression-- there are three things: human difference, prejudice, and race: race is the institutionalization of prejudice based on moving signifiers for human difference. Sometimes this involves the biological, sometimes not--I’ll explain this approach in a few minutes.

Let’s start with

Option 1, since this has been something of the way that ‘race’ is typically discussed in association with antiquity. Here we see the history of whitewashing the ancient Mediterranean at play. What do I mean--let’s ask Bernard Knox:

“The critics [of the classics and the ‘western canon’] seem, at first sight, to have a case. The characteristic political unit of classical Greek society--the polis, or city-state--was very much a man’s club; even in its most advanced form, Athenian democracy, it relegated its women to silence and anonymity. Racism in our sense was not a problem of the Greeks; their homogenous population afforded no soil on which that weed could easily grow” (12).

What did this ‘homogenous population’ look like? Here is Knox again:

"In spite of recent suggestions that they came originally from Ethiopia, it is clear, from their artistic representations of their own and other races, that they were undoubtedly white or, to be exact, a sort of Mediterranean olive color."

Lots to unpack here--like the assumption that discussions surrounding African origins of some aspects of Greek culture (to which Knox is responding) is deemed impossible, that ‘olive’ is ‘white’, that everyone who considered themselves Greek looked the same, and that this ‘Greekness’ was something that made them feel homogenous. It hardly seems possible if you know anything about the ancient Mediterranean (or Greek history).

Generally, for Knox, the Greeks are white, the Romans are white, Asia and N. Africa are white. The ancient Mediterranean was ‘white’. And it was homogenously white, which meant that ‘racism’ could not creep in. Knox, and the many classicists who preceded and follow him, did not 'see race’ in antiquity because they assume that race means somatic/epidermal (and is limited to black and white) and also because they only studied a limited scope of classical texts that do not much talk about skin color and, of course, spent very little time with ancient representations that weren’t white marble.

The assumption they made from these texts and selective artifacts was that, much as had been handed down to them from 19th century scholars, anyone whom we might call a person of color today was rare and far between in the ancient Greco-Roman world (despite spanning 3 continents) and any discussion of 'race' other than to mean 'white people' and 'black people' was anachronistic--this was despite the meticulous work previously by Frank Snowden and Lloyd Thompson on the prevalence of black Africans in Greek and Roman contexts (and the texts themselves and artifacts make it clear they were engaging with a myriad of peoples as far away as India).

It’s important to note that Knox gave this lecture, which was eventually published as "The Oldest Dead White European Males”, as a response to the Black Athena controversy, in which Martin Bernal argued for the roots of numerous Greek cultural institutions in Africa.

As Denise McCoskey has written in “

Black Athena, White Power” in Eidolon (Nov 15, 2018), the response of the classics community to the challenge of Black Athena was a ‘failure’. The failure was this:

“...by relegating Black Athena to the sphere of “identity politics” and “culture wars,” such outrage strategically allowed Classics to evade the many serious intellectual challenges posed by Black Athena.”

And that failure, McCoskey suggests, helped make classics all the more appealing to white supremacism. McCoskey concludes in her essay:

“Given such profound contradictions, classicists’ treatment of race in the aftermath of Black Athena was the epitome of self-deception and bad faith. For even as they implicitly endorsed conceptions of Greek Whiteness, classicists adopted a widespread consensus, one that lasted for decades, that the terminology of race was simply not applicable to the ancient world.”

Of course, McCoskey is talking mostly about blackness and whiteness as they can be applied to antiquity--McCoskey rejects whiteness in antiquity, but seems to maintain blackness as a viable category. It is an attempt to add the color back to the ancient Mediterranean, something that people still fight about (

especially concerning Cleopatra), despite its being closer to reality.

Perhaps, the most fruitful discussion of ‘re-coloring’ the ancient world as a practice of ‘racing the classics’ has come from Shelley Haley ("Be Not Afraid of the Dark" among others ), while others, for examples, like Frank Snowden and Lloyd Thompson (and now

Sarah Derbew) worked to explore representations of blackness in ancient Greek and Roman contexts. In these cases, we see the evidence clearly that the ancient Mediterranean was filled full of people of different skin tones. And, if we can trust the scene in Aeschylus’

Suppliants (among others), when skin color is marked out in a text, it is not (usually) held up for ridicule or engendering prejudice (see the current controversy over the

Sorbonne production)--notice here the focus is on clothing (and other customs), not on the fact that the women are black skinned, even though they specifically refer to themselves as

melanthes earlier:

King Pelasgos: This group that we address is unhellenic, luxuriating in barbarian finery and delicate cloth. What country do they come from? The women of Argos, indeed of all Greek lands, do not wear such clothes. It is astonishing that you dare to travel to this land, fearlessly, without heralds, without sponsors, without guides. And yet here are the branches of suppliants, laid out according to custom next to you in front of the assembled gods. This alone would assert your Greekness…(Aesch. Suppliants 234-45; trans. Kennedy, Roy, and Goldman).

The work of re-coloring the ancient Mediterranean from the whitewashing it has received by generations of scholars is necessary. But is it the best approach to race in antiquity or could this ‘re-coloring’ be done under the term ‘ethnicity’ or just 'reality'? This is something that needs to be judged on an individual basis by scholars--so long as we inhabit a landscape in which the question of Kleopatra’s possible blackness continues to elicit vitriolic racist responses, then the re-coloring of the ancient world should continue. And I know from conversations with colleagues teaching at the K-12 level that there is great benefit as a person of color today to see oneself in an world that has long been claimed as the legacy of whiteness. The question is, though, does it need to happen under the term ‘race’?

|

This is a very popular image

for lectures and books on race

and ethnicity in antiquity. |

Do we run the risk of reasserting a biological reality to ‘race’ if we define race in our studies of the ancient world as the very particular contemporary version of ‘epidermal race’ or ‘physiological race’? Do we reinforce the idea that 'racing' antiquity means finding non-white people when we make posters or books covers with the same janiform image over and over again? I worry about this.

What about

Option 2?

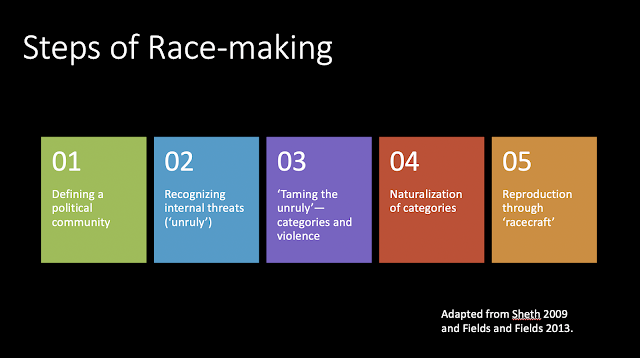

Perhaps more important to understanding whether there can be a concept of race in antiquity--or even outside of the confines of the transatlantic slave trade and modern scientific racism--is to understand that race is NOT a content signifier, but a structuring mechanism for varying content over different times and spaces. I've found Falguni Sheth's

Towards a Political Philosophy of Race (2009) really useful for thinking about this:

“Why wasn’t race considered an intrinsic feature of law? Of political institutions? Of political frameworks? For example, in much of the literature on race across the natural and cognitive sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities, the “reality” of race is still being discussed in terms of biology, empirical trends, government policies, philosophical arguments, or cultural discourse. Each of these is crucial to debating the reality of race, as well as racism and its pervasiveness. But what about the underlying framework makes the concepts of “race” and “racializing” possible? What about the discourse on race, as it has been conducted in the United States over the last 200 years, determines and re-produces certain anchors by which race is understood? Correlatively, how does this discourse obscure new, possibly more accurate ways by which to consider race, the racializing of various populations, and the way that race-thinking fundamentally infuses the most “race-neutral” of political and legal institutions? (Sheth, 2009, 3).

Sheth continues to consider how race theory in the US has been impacted by the legacy of African slavery and warns against reducing race to a black-white phenomenon only.

“Theoretical frameworks for race are also unsatisfying. We know that the legacy of slavery in the United States has viscerally affected the way that “Americans” think about race. Black–White relations often tend to determine the dynamics and general boundaries of race discourse. Yet, the presence of American Indians, Mexicans and “Californios,”the entrance of indentured servants from China and Japan, as well as continual immigration from other parts of Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East should influence how we understand the dynamic structures and production of race.”

Recognizing the limitations of defining race through modern slavery does not diminish the impact of this particular manifestation of race and racialization; rather, it helps understand better the mechanisms that allow anti-blackness to continue to be perpetuated as a tool for racism in the US and elsewhere. If we understand, as Sheth does, race not as a ‘descriptive modifier’, but as “a mode or vehicle of division, separation, hierarchy, exploitation", we can see better how institutions that seem to be, as she calls it ‘race neutral’, are actually how race itself functions. And this explains also why scientific racism reached its peak in power not while slavery was still legal, but as part of the Redemption period and Jim Crow (from the 1880s; I recommend Henry Louis Gates Jr's new

Stony the Road book on this period as well as Du Bois's

Black Reconstruction).

Sheth's questions also allow us to see the functioning of race in antiquity as well as in the medieval world, as the work of Geraldine Heng and Dorothy Kim demonstrates. Here is Heng on the topic:

“Race” is one of the primary names we have—a name we retail for the strategic, epistemological, and political commitments it recognizes—that is attached to a repeating tendency, of the gravest import, to demarcate human beings through differences among humans that are selectively essentialized as absolute and fundamental, in order to distribute positions and powers differentially to human groups. Race-making thus operates as specific historical occasions in which strategic essentialisms are posited and assigned through a variety of practices and pressures, so as to construct a hierarchy of peoples for different treatment. My understanding, thus, is that race is a structural relationship for the articulation and management of human differences, rather than a substantive content” (Heng, Invention of Race, 3).

These approaches to race are far more accurate and productive for thinking not only about the medieval worlds, but also the modern and the ancient. So, where might we see ‘race’ in this configuration as a tool for organizing human difference into hierarchies and oppressions in antiquity that can shift through time and space as the conditions of the processing of and attitudes towards and power structures surrounding human difference shift?

Race in Antiquity?

One theory that is often considered a source of racism or 'race' in antiquity is environmental determinism as found represented in the Hippocratic

Airs, Waters, Places, Aristotle, and Vitruvius. Possible, but it's not a fully developed 'theory' that actually structures hierarchies. Here are some key passages from the theory--you can see the beginnings of what will become a foundation for

scientific racism in the 19th century, but it isn't quite there in antiquity.

Here's the Hippocratic version (5th century BCE):

This is why I think the physiques of Europeans show more variety than those of Asians and why their stature changes even from city to city. The thickened seed is more prone to flaws and irregularities when the seasons change more frequently than when they remain constant. The same logic holds for character. In such inconsistent environments, savagery, anti-social attitudes and boldness tend to arise. The frequent shocks to the mind make for wildness and impair the development of civilized and gentle behaviors. This is why I think those living in Europe are more courageous that those in Asia. Laziness is a product of uniform climate. Endurance of both the body and soul comes from change. Also, cowardice increases softness and laziness, while courage engenders endurance and work ethic. For this reason, those dwelling in Europe are more effective fighters. The laws of a people are also a factor since, unlike Asians, Europeans don’t have kings. Wherever there are kings, by necessity there is mass cowardice. I have said this before. It is because the souls are enslaved and refuse to encounter dangers on behalf of another’s power and they willingly withdrawal. Autonomous men—those who encounter dangers for their own benefit—are ready and willing to enter the fray and they themselves, not a master, enjoy the rewards of victory. Thus, laws are not insignificant for engendering courage. (AWP 23)

Here is Aristotle (4th cent BCE):

Concerning the citizen population, we stated earlier what the maximum number should be. Now, let’s discuss the innate characters of that population. One could potentially learn this from observing the most famous cities among the Greeks and how the rest of the inhabited world is divided up among the various peoples. The peoples living in cold climates and Europe are full of courage but lack intelligence and skill. The result is a state of continual freedom but a lack of political organization and ability to rule over others. The peoples of Asia, however, are intelligent and skilled, but cowardly. Thus, they are in a perpetual state of subjection and enslavement. The races of the Greeks are geographically in between Asia and Europe. They also are “in between” character-wise sharing attributes of both—they are intelligent and courageous. The result is a continually free people, the best political system, and the ability to rule over others (if they happen to unify under a single constitution). Aristotle Politics 1327b

And, finally, Vitruvius (1st cent CE--though not the last version from antiquity):

Regarding the need for bravery, the people in Italy are the most balanced in both their physical build and their strength of mind. For just as the planet Jupiter is tempered due to running its course between the extreme heat of Mars and the extreme cold of Saturn, in the same manner, Italy, located between north and south and thereby balanced by a mixture of both, garners unmatched praise. By its policies, it holds in check the courageousness of the barbarians [northerners] and by its strong hand, thwarts the cleverness of the southerners. Just so, the divine mind has allocated to the Roman state an eminent and temperate region so that they might become masters of the world. (Vitruvius de arch. 6.11)

We have a sorting of the world and explanations for human difference--physical and character-wise--with a bit of chauvinism thrown into the mix, but there are no institutions or mechanisms for segregating, discriminating, etc using this theory as a basis. The same theory is functional contemporaneously in ancient China and it might be closer to racialization in those texts than what we see in the Greek and Roman since the geographic and topographic associations for ‘barbarians’ in Chinese texts are used to rank peoples into hierarchies and lead to different forms of treatment (see Yang in

Identity and the Environment in the Classical and Medieval Worlds 2015).

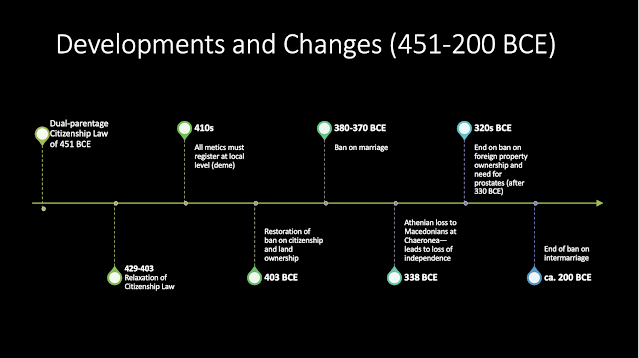

There is one particular version of environmental determinism among the ancient Greeks and Romans that I do think rises to the level of racialization and should be discussed in terms of race--the Athenian metic system.

Here is a list of the restrictions the Athenians placed on metics, often translated as either 'resident foreigner' or 'immigrant' but also included freed slaves and the descendants of immigrants and freed slaves: Metics paid a special tax, the

metoikion (12 drachma per man/family, 6 drachma for independent metic woman and children), they could not own land or house without special exemption, and there were special laws that defined their status and policed it: the

graphê aprostasiou (failure to register and pay the metic tax) and the

graphê xenias (pretending to be a citizen). These laws were policed heavily in the 4th century especially, when it seems that citizens who turned in violators would get a bounty for it--half the price of the sale of the person into slavery (the penalty for violating these laws) if convicted.

Of course, the most well-known of the metic laws was the Citizenship Law of 451 BCE, supposedly crafted by Perikles. According to this law, no child of a female metic with a citizen man could be citizen (whereas they could have been prior to the law). This double-descent law was, as far as we know, the first of its kind since it required the woman as well as the man to be citizens. The law was accompanied by a rise in rhetoric and public representation of

autochthony, the ancient idea of indigeneity, which the Athenian, somewhat uniquely among the Greeks, promoted as their origin.

While most other Greek poleis had migration stories as their foundations, the Athenians suggested they were 'born of the soil'. The Citizenship law, with its emphasis on purity of birth to preserve this autochthonous descent is our earliest 'blood and soil' ideology. Further, we see accompanying this praise of Athenian purity a language of disease and infection attached to metics--whether it is Phaedra in Euripides' play

Hippolytus or in the law courts, this language of infection and purity was used to segregate all non-Athenians into this category of 'metic' that embodied institutional oppressions, dehumanization, and systemic abuses based on the supposed supremacy of Athenians over all others--Greek or non-Greeks [1]. This was a racialized system and much closer to Sheth's definition of 'race' above.

ETHNICITY

I’ll start this section with an anecdote: I was at a bar one night with a colleague in religion and her partner, who was visiting from Canada. We were talking about race and ethnicity in antiquity (they do ancient Mediterranean religions). The partner of my colleague objected to the use of ‘race’ for discussing antiquity. Fine. Lots of people say this. But it was his reason that I remember:

“Race is political, ethnicity is academic.”

Oh, so incorrect, my friend. So incorrect!

Ethnicity is a 20th century term that seems to first appear in Weber’s works (around 1906). Weber’s coinage includes the caveat that ethnicity should refer to customs and biology should not be considered a foundation for group identity unless that was somehow a shared characteristic of the group--there are ample biologically or kin based peoples who did not consider themselves of the same group--customs should be the common denominator.

As Jonathan Hall discusses in the introduction to

Ethnic Identity in Ancient Greece, the term ‘ethnicity’ was taken up as a replacement for ‘race’ by many scholars based on recommendations found in the

UNESCO 1950 Statement on Race. It wasn’t necessarily intended that scholars maintain the work of preserving racism under the guise of ethnicity studies, but this is what happened in some cases (and is happening again with the new genomics; See the work of Kim Tallbear, Dorothy Roberts, and Ann Morning for discussions). Omi and Wyant comment in their most recent edition of Racial Formation (2015, x) as follows:

"In many ways the post-World War II social sciences disciplines still reproduce white supremacist assumptions…In prevailing social science research, race was conceptualized and operationalized in a fixed and static manner that failed to recognize the changing meaning of race over historical time and in varied social settings."

Meaning, as Dorothy Kim (in a forthcoming essay) summarizes from Omi and Wyant in discussing race in medieval studies:

"In this way, using the term “ethnicity” when what is being discussed is race, structural racism, and racialization, is to uphold a white supremacist political and neoconservative position that is itself being discussed as racist frame (i.e. colorblind). Therefore, recent ambiguity, or the eschewing of the term “race” in medieval critical discussions for “ethnicity,” ignore not only the history of the social sciences in Western academic discourse of over a century, but also either because of willfulness or ignorance, gloss over the political stance the use of the term engenders."

The decision to take up the term ethnicity was EXPLICITLY political and many fields, anthropology in particular, have come to understand that this decision had serious consequences in that it allowed racism to continue to sit below the surface and blossom uninterrogated.

If we recognize that ethnicity was a term developed in the 20th century and was, essentially, taken up as a substitute for ‘race’ after 1950, and that many scholars have done so as a way (intentionally or not) to avoid the unpleasantness of addressing contemporary race issues, should we actually just talk about 'race' and not 'ethnicity' as a more authentic and less ‘political’ and ‘colorblind’ concept?

This is, in fact, was Denise McCoskey’s decision in her book

Race: Antiquity and its Legacy as a way to try to force the issue.

BUT race and ethnicity are not actually interchangeable. If race means talking about systems of oppression based on variously constructed packages of human difference in different contexts, then we still need a word to talk about the cultures and societies of various peoples in particular geographic contexts in antiquity. Especially when those groups are structured around descent (real or imaginary, as Jonathan Hall articulates it).

This is what makes that Old Herodotus passage (8.144) so appealing for those of us who want to talk about ethnicity in antiquity!

Athenians: “It was quite natural for the Spartans to fear we would come to an agreement with the barbarian. Nevertheless, we think it disgraceful that you became so frightened, since you are well aware of the Athenians’ disposition, namely, that there is no amount of gold anywhere on earth so great, nor any country that surpasses others so much in beauty and fertility, that we would accept it as a reward for medizing and enslaving Hellas. [2] It would not be fitting for the Athenians to prove traitors to the Greeks with whom we are united in sharing the same kinship and language, together with whom we have established shrines and conduct sacrifices to the gods, and with whom we also share the same mode of life.”

Here is what I had to say about this passage from the entry on "Ethnicity" in the

Herodotus Encyclopedia (forthcoming; edited by Christopher Baron with Wiley-Blackwell)--see this previous

post for my frustration with Herodotus on this front:

"Herodotus’ network, therefore, seems to embrace linguistic, cultural, political, and descent elements. At Hdt. 8.144.2-3, his Athenians express their relationship to their fellow Greeks as rooted in shared descent (homaimos), language, religious practice, and cultural ethos. Thomas (2000) sees this list of characteristics defining ‘Greekness’ (and thus ethnicity) as ambiguous and unreflective of the reality embedded within the Histories themselves of any shared sense of Greek ethnicity. Munson (2014) emphasizes the privileging of custom given the shared kinship evident throughout the Histories of distinctive groups. If we view these elements as part of a network, however, we need not view the absence or elevation of any of single element at a given moment as defining an absolute Herodotean concept of ethnicity."

and

"The list Herodotus’ Athenians provides us, then, at 8.144 in this key moment in his histories of what group identities entail may be the most explicit definition of ethnicity, but a specifically Athenian one as there are numerous stories throughout the text that express variations on what constitutes group identity and how these identities are formed and maintained. Herodotus’ history offers various ways to construct identities that recognize differences between ethnic groups even as they share some commonalities--ethnicity as contingent identity shaped according to changing needs and contexts (Hall 1997; Demetriou 2012). Herodotus also allows for the multiplicity of identities that any group or individual has--ones ethnic identity could include an ethnos, a genos, a phylla, and a polis depending on the circumstance and need. Ethnicity for Herodotus, as for modern scholars, “is a concept with blurred edges” (Wittgenstein §71)."

A recent discussion of ethnicity in antiquity is Erich Gruen’s 2013 article “Did Ancient Identity Depend on Ethnicity? A Preliminary Probe” (Phoenix 67: 1-22). There he attempts to argue that the ancient world did not really have any concept of ethnicity as we understand it. It is an interesting take, mostly because Gruen rejects decades of scholarship on ethnicity and even the originating definition of ethnicity by its coiner, Weber, to define ethnicity exclusively as shared lineage—the one thing Weber said when he coined the term was NOT necessary unless it was integral to the cultural character and self-definition of the people. Gruen goes on to say that ethnicity is, for him the equivalent of ‘race’. Of course, defining ‘race’ as ‘shared descent’ is itself a problem, i.e. as my undergraduate students pointed out last years when I asked to read the article, “Gruen doesn’t know what race is” and, as his bibliography shows, he doesn’t seem interested in learning.

Most other scholarship understands ethnicity closer to its roots and closer to the definition Herodotus has his Athenians provide—as a people linked through shared customs who may or may not share descent (real or imaginary). And ethnicity is, as a result, mutable and flexible. This makes ethnicity a concept with clear relevance and use value for the study of antiquity, as it allows us to look both at peoples as they self-defined and as they defined others through customs and helps us make sense of the hundreds of texts and images from antiquity (from the Mediterranean to Egypt and China and India) that describe and discuss the practices of those they considered ‘other’. There has been a tendency in recent history to conflate ethnicity with the nation-state, but this is a mis-approximation and one that has failed both for antiquity and the modern world.

Ethnicity gives us a language and structure to think about the facts of human self-grouping and sorting and the recognition of others doing the same thing. We should not throw the term out despite its political origins, but we should not pretend it can serve to cover the territory that ‘race’ is needed to do either--i.e. institutionalized segregations for the sake of oppression based on moving signifiers of what counts as 'difference'. My suggestion is that we keep both and recognize that as with any terms we use to translate the ancient world, there will never be exact equivalences. We just need to be clear to define our terms.

The question remains--is there 'race' and 'ethnicity' in antiquity? Can we use these terms to talk about identity formation by ancient peoples? What do we benefit or lose?

We need to acknowledge that for many in the ancient world, there may have been multiple functioning ethnicities or other identities--sometimes they were Greeks, sometimes Athenians, sometimes Ionians--and that this could change--just as Athenians had been, according to Herodotus, Pelasgians, until they changed to being Hellenes. Or how many people living within the Hellenized post-Alexander world or Roman empire could be functionally Persian, Greek, and Roman (for examples) at the same time.

We can’t ever assume that because a language doesn’t have a term for a concept that their aren’t places where that concept is functional. What we now call ‘race’ in common practice (i.e. in our census), is not what ‘race’ actually is in practice--it is a manifestation of a process that seems to occur transhistorically and transculturally as a way for dealing with the anxieties and fears that seem to accompany encounters with difference. We should expect to find ‘race’ and ‘ethnicity’--our current terms for this process--in other places and times and in trying to understand how it functions in antiquity, we can, hopefully, understand better how it impacts us now.

We are long past a time (centuries, in fact) when we can pretend that any choice we make in these debates is not political. Our best hope is to try to be as accurate as we can and use carefully defined language that does the least injustice to those who have lived under the weight of prejudice and racist hate in the modern world while also trying to build the most accurate view of the ancient past.

[1] I've written about this in my book Immigrant Women in Athens and Susan Lape lays out some of the dynamics as well in her 2010 book Race and Citizen Identity in the Classical Athenian Democracy. You can also read some previous discussions of this system here and here at Eidolon with links to ancient sources, etc.