A few months ago, I finished a chapter for an edited volume on the concept of foreignness in antiquity on the Athenian system of metoikia as an enactment of race in antiquity. I've been working on this idea now for about 4 years, trying to find ways of expressing 1. what we mean when we say 'race' in any context, 2. whether it can be seen in antiquity (contrary to the beliefs on both the majority of classicists and of scholars of modern race), and 3. how a model of race in antiquity might look. Many years ago (spring of 2019), I posted a talk I'd given at Duke-UNC Center for Late Antiquity that attempted a beginning of articulating what this might look like. The chapter on metoikia is the culmination of that work.

In this blog post, I am going to provide a shortened version of that chapter that will hopefully lay out the model in an accessible way. I also gave a talk in this shortened form at a recent Monitor Racism conference. The audio recording can be found here (I begin at around the 2hr 11min mark. Denise McCoskey precedes me with a discussion of the history of race in the discipline of Classics). The images provided here are from that talk as is much of the text. This work builds from my last book, Immigrant Women in Athens and looks forward to research in other aspects of race and ethnicity in antiquity that I am currently working on or planning.

I present this abridged version of my model and research as a proposal for what studying race in the ancient past can offer to understanding race in the modern world, but also as reflection of what deep engagement with critical race studies can help us understand about the ancient world as well. We must simultaneously dismantle the centuries of accretion of white supremacist world view from our understanding of the ancient past while also seeing where modern race systems borrowed and adapted their own ancient models. We have to be in conversation with, not borrowing from, modern critical race, if we want to change our discipline and also more accurately understand the past.

I am willing to share the full version of this chapter for classroom or research use. I am still awaiting revision suggestions from the editors, so it is not yet in its final form. Contact me, if you are interested.

***

Let's start with who or what was a "metic". It isn't as easy a thing as we think. The term is frequently translated as either "resident foreigner" or "immigrant", though you can see from the the slide below that "immigrant" is a metaphorical use for many people who fell into this legal category. Essentially, it was a legal category that sat in between a citizen and the enslaved in Athens (and in some other Greek poleis, but we don't have as much information about how their systems worked). It contained free people, but free people whose status as "free" was not inalienable.

When the category was first established, it was defined by a series of restrictions that set those counted as 'metics' and those who did not apart from each other. Central to the definition of metic is that it encompasses any free person in the city who has been there for about a month and intends to stay longer. They must register themselves with a local official (the polemarch) and pay a special tax. This separated them out from citizens (who did not pay a special personal tax), enslaved, and visitors from other places, including merchants just passing through. These initial restrictions will increase over time, which I will discuss below.

|

Proxenia = honorary quasi-citizenship, isotelia = tax equality with citizens (don't have to pay the metoikion), enketesis = right of property ownership.

|

These are the basics. Now, for the details and how this legally defined group of people from ancient Athens can help us in articulating a transhistorical concept of race.

Metoikia as Race

Scholars have used race, a concept given to a frustrating multivalence, with different meanings when discussing the ancient Greek world. I must clarify both what I do not mean by ‘race,’ as well as explain the technical meaning I use here, adapted primarily from the work of Falguni Sheth and Karen and Barbara Fields--though their own definitions are rooted in long histories of critical race. Race as I use it here is a technology or doctrine of population management that institutionalizes ethnic prejudice, oppression, and inequality based on imaginary and moving signifiers for human difference, signifiers that manifest differently in different times and places (i.e. it is transhistorical and fluid).

The imaginary and moving signifiers in the case of the Athenian and metic eventually follow what Fields and Fields define as the ‘doctrine that nature produced humankind in distinct groups defined by inborn traits that its members share and that differentiate them from the members of other distinct groups.’[1] Because these groups are imaginary, they can be constituted from those who might, in a different classification system, be very diverse.

Race, then is the doctrine or technology for creating distinctions in institutions. In our Athenian case, I will focus on law thats crafts political institutions that create and then support a doctrine of inherent superiority of the citizen population while casting others as inferior. In this framework, we might define ‘racism’ as the ‘practice of applying a social, civic, or legal double standard.’[2] For the Athenians, the double standard inheres in the application of law (and particularly the right to enslave) between citizens and metics; racism is the application of law to enforce distinctions between political classes and their risk of experiencing state-moderated violence. The distinctions between Athenians and metics are then reproduced through what we call ‘racecraft, ‘the practical, day to day actions that reproduce the imaginary, pervasive belief in natural distinctions between the groups.’[3] Some examples of racecraft would be daily reminders of second class status like having to pay special taxes: the metoikion itself, ‘foreigners only’ taxes for using the port (pentekoste) or selling in the markets (xenika tele),[4] in limitations on contracts and ownership, bans from civic spaces, or segregation when participating in city rituals.[5]

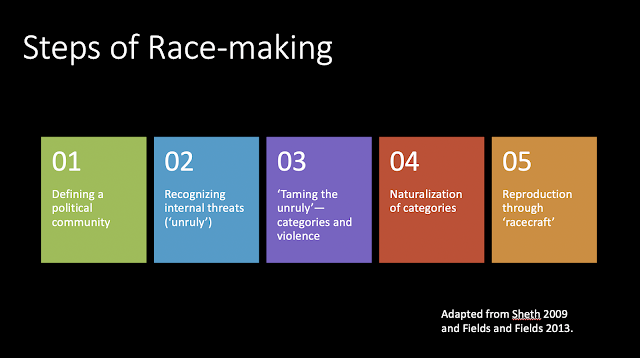

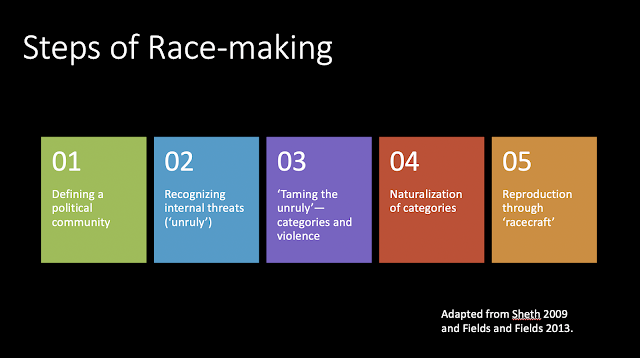

Race forms and reproduces through a process that begins with defining a political community. This community then must recognize internal threats, which Sheth refers to as the ‘unruly’.[6] This recognition instigates a ‘taming of the unruly’ through the imposition or refining of laws that have the threat of violence as their mechanism for enforcement. These laws create distinctive racial categories into which the community is sorted. Next, the racial divisions are then naturalized[7] (or justified) within the community, frequently through narratives of biological sameness or purity, giving rise to ‘race.’ The system is then reproduced through the ‘enframing’[8] of vulnerability and violence as the defining characteristic of the group’s place within the community and ‘racecraft.’[9]

This understanding of race is different from what we might consider ‘folk’ ideas of race in a modern context, what has been called ‘somatic’ or ‘epidermal’ race or ‘bio-race’.[10] This modern folk definition appears within my framework as a signifier of difference, but one that is historically contingent—it may not mean in one context the same as it means in another. For example, the specific modern signifiers of skin color, used as a shorthand to change racism into ‘race’ in the modern US, is not relevant as a component of race, racism, or racecraft in Greco-Roman antiquity.[11] Any biological fiction used as shorthand for ‘race’ is created as part of that process and is just that, a shorthand.

By focusing on the process and technology as race, we can retain the term ‘ethnicity’ as productive and meaningful in discussing antiquity.[13] When I use the term ‘ethnicity’ or ‘ethnic’ in discussions, I am referring primarily to self- or other-defined groups based on ideas of shared culture, language, or political affiliation that are not embedded within legally enforceable hierarchies of oppression. Here we might think of the difference between the two images above. One tomb, on the left, is for a woman identified through her "ethnic"--she is Demetria of Kyzicus. The image on the right is the tomb of Melitta, identified as the daughter of an isoteles, a privileged status granted to some metics in Athens. The tomb on the left was likely put up by a member of Demetria's family who self-identified as Kyzican. The tomb on the right was likely put up by the Athenian family Melitta worked for who identified her through her place within the Athenian metic system. The tomb on the left tells me about the ethnicity of Demetria. The tomb on the right tells me where Melitta fit in a racial hierarchy.

In order for race to exist as most scholars of critical race suggest, it must exist within a political order, not simply as an abstracted category. Without the creation of hierarchies and the ability to enforce oppressions, we have prejudice or ethnocentrism—it is the power of a state or institutions to enforce socio-political Otherness that determines race. Ancient Athens eventually used a myth of indigeneity (autochthony) linked to biological descent as their justification for the segregation of their population, but it is the institutionalized (threat of) violence for enforcing a form of segregation or caste that makes the case for metics a type of ‘race’ in antiquity.

For the Athenians, the metic was perhaps the most salient ‘other’ in their daily lives in so far as they had another free population against which to rank themselves. It was certainly more operational than than the ‘barbarian’ and it cut across and dismantled on a regular basis the notion of unified “Greek” identity. Demetra Kasimis has discussed this aspect of the metic in the political theory of Plato (mostly) in the 4th century, for those interested.

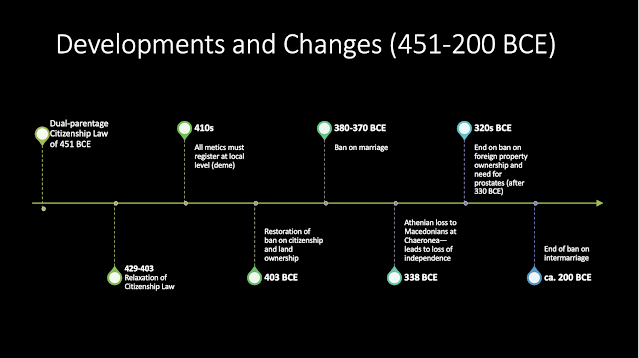

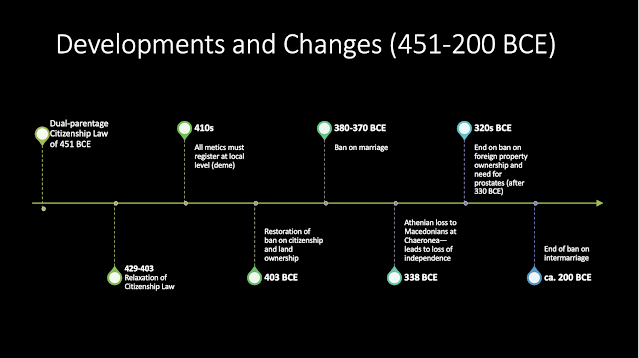

How did the ‘metic’ (and so the ‘Athenian’) became racialized? For, it is my contention that the Athenian is only racialized as a result of the process that created the metic.[14] We see the following historical steps: first, the constitution of the Athenian demos (i.e. male citizens) through patrilineal citizenship (510 BCE), next, the creation of the metic as a legal category (ca. 460s BCE), followed by dual-descent citizenship (451 BCE), and, finally, the elevation of the myth of autochthonous ancestors to a myth of full Athenian indigeneity and ethnic purity (starting in the 430s BCE).[15] Later laws, like the requirement for deme registration (410s BCE), reinstatement of the Citizenship Law (403 BCE) and the ban on marriage (380s BCE), are refinements and reassertions of the system. In the first step, we see the construction of a political community, in the second, the identification of what Sheth refers to as ‘the unruly’, a group within a community identified as a threat to the political order. This is followed by the group’s segregation in an attempt to reduce their potential harm to the political order.[16]

The physical and even cultural sameness of the metic, their Greekness or, even more broadly, Mediterraneanness, may be what made the ‘metic’ threatening; there were only subtle differences that could be sensed, but not easily identified.[19] In the case of the metic, the original unease centered, perhaps, on the basic premise of them not being citizens. We do not know how large this population was.[20] Whatever it was, in consciously creating and defining through legal restrictions a category beyond ‘not citizen’ and designating certain individuals within the community as members of it, the Athenians succeeded in also re-emphasizing their own identity as citizens and the political order upon which their own status rested. They continues to shift the laws over time to adjust policy as prejudice was naturalized.

The next phase of the process of racialization after ‘taming the unruly’ is naturalizing the distinctions. The original definition of metic rested on a patriarchal justification; the citizenship law focused on a more purely biological justification. This shift in policy and in definition of the legal category crafted the underlying framework for the racialization of Athenians through the metics. The ancient rationales for the passage of the law (“too many citizens,” Aristotle & Plutarch) are unsatisfactory as a full explanation. I think, in fact, an important element came from an upswing in prejudice, prejudice that resulted from viewing the metics as a distinctive class after the 460s when the legal category came into being--racist ideas and policy precede race. This increased prejudice led to the development of a concept of Athenian indigeneity (autochthony), which functioned as the naturalizing, retroactive justification for the metic’s status.

Although laws initially segregated metics, the idea of Athenian autochthony naturalized the category of citizen, grounding the fiction that the law simply reinforced a division made by and through biology or the environment.[21] This naturalization process appears reasonable and rational when we recognize that indigeneity in Athens was a type of environmental determinism, a broadly held idea that the geography, topography, and climate of places shaped and defined the peoples who resided there.[22] The Athenians, indigenous to the land and imbued with certain characteristics from the land, came to identify themselves with a closed kinship group invested in an idea of a ‘real’ or ‘pure’ Athenian.[23] Autochthony myths were the metaphorical manifestation of this doctrine, a racial doctrine, as Susan Lape has argued, that demonstrated the superiority of the Athenians.

The process of racializing the metic did not end with either the passing of the 451 Citizenship law nor with the naturalization of the metic as inherently and threateningly different that we see emerging with the development of indigeneity and autochthony as identity. While much scholarship has treated the 451 BCE citizenship law as a ban on marriage between Athenians and non-Athenians, it likely did not. Rather, the evidence suggests that marriage was not banned between citizen men and non-citizen women until the 380s. And, in fact, the law went either unenforced or even was relaxed or repealed for decades during the Peloponnesian war.[24]

In 403 BCE, however, the laws requiring that Athenian citizens have two Athenian parents and restricting land ownership to only Athenian citizens were reinstated as foundational laws of the newly revived democracy after the brief government of the Thirty, a reactionary oligarchy that had aggressively and violently dismantled the Athenian democracy in 404 BCE.[25] In the aftermath of this reinstating of the law, the demarcation between metic and citizen became increasingly harsh (eventually leading to the marriage ban in the 380s), suggesting that the prejudices that inhered in the status of metic that required segregation previously did not disappear even under the extreme circumstances of the wars. Relaxing the laws and allowing metics (and even enslaved persons) access to citizenship may have been blamed, in part, for the loss.[26] Once the metic had been racialized and this racialization naturalized, they would always be deemed inherently threatening. That the metic population in the 4th century was increasingly made up of formerly enslaved persons may have contributed to this prejudice.

Because of the variety of persons and origins and statuses that made up the metic class, however, and although metics were defined as a single class by law, the laws were not experienced equally by all metics. While scholarship on metics has done a good job at recognizing class distinctions among metics and acknowledging that privileges offered to metics rarely accrued to those who had been freed enslaved persons or working class metics, most scholarship on ‘metics’ talk of the laws and structures surrounding them as if they are default male (i.e. gender neutral) and also absent most forms of ethnic prejudice.[27] But this was not the case for any but the wealthiest or most useful male metics and mistakenly assuming that prejudice diminished because more elite men were granted access to citizenship points to why we need intersectional analysis. Metic was a racialized category that included lots of different groups. It was founded upon and enforced through threat of violence, which some metics were more vulnerable to than other. Nonetheless, even those who did not directly experience that violence were conditioned by its possibility.

Race and Violence

By 403 BCE, the legal structures were in place for the perpetuation and reproduction of race in Athens through the metic. In other words, the process of racializing the metic (and the Athenian) had been mostly completed. The reproduction of race, which may be understood through the ‘racecraft’ of everyday life, happened in many ways but often through violence or the threat of violence. To be a metic was to be vulnerable to such violence. The penalties (enslavement and execution) enforced segregation and submission to the metic system in Athens, classifying the metic as inferior to the Athenian and closer to enslaved. Metics received only alienable humanity, according to Jackie Murray’s usage of race.[28] Discussing Homer’s Odyssey, Murray places race and ethnicity on a continuum, with ‘ethnic others’ granted a higher level of humanity while racialized groups, who are further away from the inalienable humanity of the dominant group, are granted less humanity. Thus, in the Athenian context, a Milesian visitor or business partner was closer to Athenian to the extent that they still functioned as their ‘ethnic’ self. But once they became ‘metics’ their racialized status meant that they were subject to Athenian institutional violence in ways visiting foreigners were not. Metics could not appeal to shared Ionian or Greek identities or even to being from an Athenian colony to mitigate their being metics. Such distinctions were erased once they became a metic in law and the Olynthian was no different from the Thracian or the Skythian (or any other ‘barbarian’) in their status and their being subject to state violence.

Obviously, not all metics (and, in fact, the majority) would ever have experienced the violence of being sold into enslavement or being executed for breaching their status. They were also, as Ben Akrigg has pointed out, theoretically subject to torture for evidence.[29] We do not have evidence that this was very common, but, this is one of the fundamental characteristics of race—the experience of violence is not necessary, only the threat, which is validated by the fact that others within the group do experience this violence as part of their everyday existence and within the scope of the law.[30] The threat is what allows for those metics with privileges to have them and to feel them as privileges and even argue against the interests of their class as a whole in order to maintain them.

Wealthy metics and those who arrived in Athens as refugees were granted a series of privileges within the scope of law that could mitigate their vulnerability to violence. For some metics, living in Athens approached citizen status, but without assembly attendance and voting: they performed liturgies; they dined with (and in the 5th century still intermarried with) their social peers; they participated in the Panathenaiac procession. And the reward system of privileges, like grants of isoteleia and enktesis, rewarded those metics who not only followed the rules but were deemed most useful to the polis.[32] They became, in some ways, ‘model minorities’, whose privileging could encourage them to become complicit in the enforcement of violence on others within the metic group.[33]

The vulnerability to violence inherent in the status of metic did manifest on a daily basis for metics who were not of the privileged economic classes or who had not been granted special status through grants to specific refugee groups, because of their gender, economic status, or status as formerly enslaved. As I demonstrated in Immigrant Women in Athens, women metics were especially vulnerable to all sorts of violence in law and through loopholes in the laws.[37] Let me offer an example (you can read Chapters 4&5 of Immigrant Women for many many examples). The so-called phialai inscriptions. These are most likely inscriptions that record dedications made by metics who had been charged with not registering or paying their tax, but successfully defended against it.[38]

Extant are over 400 names, including men, women, and children, some appearing as families. The inscriptions list over 100 different professions, all of them what we would call ‘working class.’ The inscriptions are broken and only a small percentage of those originally carved are extant. They record, likely, about seventy or so years of cases. Hundreds of them. Any citizen could prosecute them and they had incentives. What this suggests is that metics, especially those without wealth or connections to citizens, could be subjected to regular surveillance by citizens, could not trust that a citizen would not turn on them, and were always vulnerable to the violence inherent within their legal status.[39]

I would like to end with a quotation from Falguni Sheth, who for me, sums up what the process in Athens looked like over the course of the 5th -4th centuries, a summary which I think would be even more obvious if I could provide for you in this abbreviated space the dozens of legal cases and acts of violence leveled against metics, especially women. Sheth says:

And so we see through any number of legal judgements, race is never merely about ‘race.’ It is in the drawing of the lines between ‘evil beings’ and ‘moral beings,’ between persons and nonpersons, human beings qua citizens and those who cannot be citizens because they are ‘not human like us,’ where we find the salience of race. Understood as a vehicle by which to draw and redraw the boundaries by which select populations are assured the protection of the law, race becomes deployed as a technology. It is when we understand it as a technology that we begin to understand how race locates and domesticates the ‘unruly,’ and in so doing, ‘reveals’ the apparatus by which the normative ground of racial classifications was once naturalized and concealed.[43]

My hope with this analysis is that if we can see it happening clearly in the case of metics in Athens, we can better articulate and reveal how it functions at the level of institutions today and elsewhere in our histories, where too many people and governments insist that because race is not a biological fact, it somehow isn’t still real and embedded in our laws and everyday practices.

Endnotes

[1] Fields and Fields 2013, 16. This is their definition of ‘race.’

[2] Fields and Fields 2013, 17.

[3] Fields and Fields 2013, 18-19.

[4] Blok 2017, 273. Blok sees these as reasonable taxes for non-citizens and does not agree with Whitehead’s assessment that the tax was meant to be a humbling and even humiliating reminder of their second-class status.

[5] On marching in the Panathenaia as a mark of privilege, see Wijma 2014. Obviously, the metics selected would have been from among the privileged class. This does not make the segregation a mark of metic privilege. See Fields and Fields 2013, 33-4 for a discussion of sumptuary laws and enforced clothing distinctions historically as racecraft.

[6] “This is the element that is intuited as threatening to the political order, to a collectively disciplined society. As the term suggests, this element threatens to disrupt because it signifies some immediate fact of difference that must be harnessed and located or categorized or classified in such a way so as not to challenge the ongoing political order” (Sheth 2009, 26).

[7] After the initial ‘processing’ of the unruly through the production of certain categories, the process—the political context—of classifying becomes forgotten, concealed, or reified. Thus, it appears as a ‘natural foundation’ for racial categories (Sheth 2009, 28).

[8] “Enframing refers to the cultural, political, social, moral, methodological apparatus that both shrouds and infuses our current quest for the meaning of race” (Sheth 2009, 35).

[9] The enframing of race exemplifies not merely division, but a method of using the unruly as a way to “cultivate vulnerability or the threat of potential violence among its populace in connection with a certain mode of political existence, namely one in which our relationship to society must be understood as one of vulnerability and violence” (italics original) (Sheth 2009, 36). For ‘racecraft’, see below.

[10] On the idea of bio-race, see Fields and Fields 2013, Ch. 2, especially discussion of the idea of ‘blood’ equaling ‘race’.

[11] Somatic race, however, has been usefully deployed, e.g. by scholars such as Shelley Haley, Frank Snowden, and, now, Sarah Derbew (both in her dissertation and now in a forthcoming book), to undermine and reverse the ‘whitewashing’ of the ancient Mediterranean. Scholarship and popular representations of the ancient world since the 19th century have been engaged in this ‘whitewashing,’ and we need to engage with the work cited earlier and produce more.

[12] See Lape 2010, 1-7 and 31-52 for her conceptualization of race through Appiah’s idea of racialism, which she calls a ‘quasi-biological paradigm.’ For my own earlier conceptualization of race in early Greek thought, see Kennedy 2016. I would not now use the term ‘race’ to discuss genealogies and descent outside of enforceable hierarchies, but ethnicity. I agree with Jácome Neto (2020) that what many scholars are discussing under these headings is not ‘race’, though I disagree that ‘race’ is a particularly modern concept. See Heng 2018 for thorough discussion and examples of pre-modern race.

[13] pace McCoskey 2012, 31 who uses ‘race’ exclusive of ethnicity to ‘force[s] us to confront our all-too-frequent idealization of classical antiquity. In the recent Oxford Classical Dictionary entry, McCoskey uses ‘race’ for any system of classification regardless of the ability to enforce any hierarchy based on the classifications and fuses etic and emit forms of identity formation. Yet many scholars of modern race reject its presence in antiquity precisely because the dominant theories of human variation (environmental determinism, descent-based, cultural) lack any institutional structures for enforcement.

[14] Lape 2010 provides a strong argument for the Athenians as ‘racialized,’ but within a framework of ‘before race.’ She devotes only 5 pages to the metic.

[15] Shapiro 1998.

[16] Sheth 2009, 26.

[17] Kennedy 2014, p and forthcoming (a) 2021. On the relationship between Suppliants and the development of metoikia, see Bakewell 2013.

[18] A primary argument of Kennedy 2014.

[19] “That which is unruly can be evasive enough to be ‘intuited’ or ‘felt’ rather than seen or perceived—because the ‘intuition’ is one of ‘danger’” (Sheth 2009, 26). We might here think also about the statement in the Old Oligarch that one of the problems of Athenian democracy was the impossibility of knowing the difference between a citizen and a slave (citation). Missing from the equation, of course, is the metic, who would also be indistinguishable.

[20] Efforts to calculate the metic population over time have been attempted by Patterson 1981 and then Watson 2010. Both population estimates were used in the service of arguments for the date of the creation of the metic as a class as if once the threshold of foreigners in a place reaches a certain level, citizen anxiety demands action. On the psychology of this phenomenon in the contemporary US, see Craig and Richeson 2014.

[21] The scholarship on Athenian autochthony is large. See Roy 2014 for a recent summary of the scholarship. Most scholarship following Rosivach 1987 have generally accepted his timeline of the development of the concept, but see also Blok 2009, 251-75. I find Loraux 2000 to be the best discussion of the ideology underpinning autochthony. Though see also Lape 2010, 95-136, who discusses it through the myth of Ion.

[22] On archaic and classical concepts environmental determinism, see Kennedy 2016 and Kennedy and Blouin 2020. For discussion of the broader reach of environmental determinism theories in antiquity, see the essays in Kennedy and Jones-Lewis 2016.

[23] For specific ways the autochthony myth appeared in Athenian public discourse and in the landscape, see Clements 2016 for discussion of the Erechtheion, autochthony, and the landscape of the Acropolis. On the visual catalogue of autochthony on pots, see Shapiro 1998. On funeral orations and autochthony, see still Loraux 1986. On Euripides’Ion and the deployment of myths, see Lape 2010, 95-136. The discussion in Kasimis 2018 follows a similar path to Lape’s.

[24] See Kennedy 2014, pp for discussion and bibliography.

[25] On the basic outlines of Thirty and restoration after the civil war, see, Carawan 2013.

[26] Bakewell 1999. See also Lape 2010, 262-74.

[27] E.g. Rubenstein 2018. Carugati 2019a.

[28] Murray 2020.

[29] Akrigg 2015, 166.

[30] As Sheth writes: “When race is deployed through law to demarcate distinctions between populations, violence per se is not immediately manifested through these categories. But more accurately…the sheer capacity to instantiate such distinctions gains its power of enforcement through the potential violence that is inherent in it” (Sheth 2009, 37).

[31] Carugati 2020.

[32] Carugati 2019a, Ch 4.

[33] See Lee 2020 for definitions and debates over its efficacy as a concept.

[34] Bakewell 1999 discusses this period from Lysias’ perspective using Lysias 12 and 31. See also Wolpert 2002.

[35] On the ancient debates, see [Arist.] Ath.Pol. 40.2; Aesch. 3.187– 90.

[36] Loraux 2002, 246-264 is a most illuminating discussion of the restoration of the laws in the context of the amnesty, though see also Wolpert 2002 and Carawan 2013, though Carawan hardly mentions metics.

[37] See Ch 4 in particular for discussion. My analysis of violence as it impacts non-citizen and working-class women is inspired primarily by Crenshaw’s legal concept of intersectionality.

[38] See Meyer 2010 for a detailed reappraisal and updated edition of the inscriptions.

[39] There are also cases of men recognized by their demes as citizens being challenged under the law of graphe xenias. Two particularly interesting orations recording or referring to these cases are Dem 57 (Euxitheus) and Isaeus x (. ). In the former, the speech is his defense of his citizenship and we do not know the outcome. The latter is an inheritance speech and we are told that the father of the heiress was charged but won his case (if only by a slim margin).

[40] Fields and Fields 2013, Ch. 2.

[41] As Schapps 1977 has demonstrated, the naming of women in public for a like the courts or stage was typically reserved for women who were being targeted as ‘not respectable’ and so being classified in these discourses as women who could be targeted. His arguments have been frequently misinterpreted as saying that the women named were somehow shameful. For further discussion, see Kennedy 2014, pp and Kennedy forthcoming (b) (specifically on the courts).

[42] Although there is no space to discuss it, Apollodorus’ attacks on his brother Pasikles (a natural-born citizen), mother Archippe (a woman with quasi-citizenship status; see Kennedy 2014, pp), and step-father Phormio (also a naturalized citizen and former enslaved person) are remarkably enlightening in understanding how the Athenian legal system can be used to police race.

[43] Sheth 2009, 38.