A theatre group at the Sorbonne has been making headlines after a production of Aeschylus' Suppliants they were preparing for was shut down by protestors. What?! This sounds CRAZY! Were the protestors opposed to a possible message of the play as welcoming refugees and immigrants (as seems to have been the point with the Sicilian staging in 2015)? No. They were protesting the play as racist and they have a point.

Here's a picture of the performance (possibly last year's?). See if you can tell me why they might think something was awry:

Notice anything about the actors? Hint--this is a photograph, not a coloring book. That stuff on their skin is #blackface.

Since the protestors blocked the performance, there have been a series of statements from the uni and the director with excuses replete with condemnations of the protestors. John Ma sums it up on a Twitter discussion about it:

Last year's performance apparently had been done in #blackface and, really, do actors do dress rehearsals in #blackface if they are going to wear masks in performance? Why would they not practice instead in the masks and not go through all the time and effort of donning #blackface? And if the director was really interested in capturing the dynamics that emerge from remembering that the Danaids are in the play black-skinned, why not cast appropriately?

Because, one of the remarkable things about the play is that, although the Danaids explicitly refer to themselves as "black" ('black, sun-beaten people" μελανθὲς ἡλιόκτυπον γένος lines 154-5), it is not considered an important mark of their difference at all when they arrive in Greece from Egypt. When the Argive king Pelasgos first sees them, he thinks they look very foreign, but doesn't even notice their skin color:

Additional irony? The thing that marks them as foreign in Aeschylus is their clothing. See anything in the pictures about their clothes? Yep--Greek-style. This director has reversed Aeschylus.

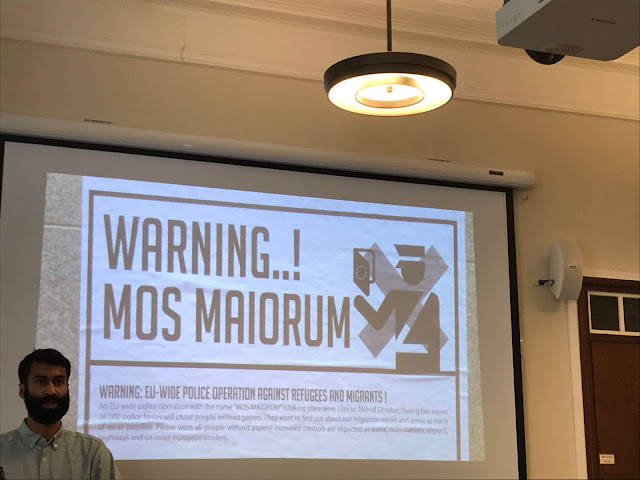

Of course, there is much else to be discussed concerning the reaction to the play. The protestors are reacting to the #blackface and placing it within the context of France's history of colonialism (and its 'official' state denial of racism as a phenomenon in France):

Over the last two weeks, I've given a series of talks on Aeschylus' play and asked myself the question of whether in its original context it was a play about welcoming refugees or about the benefits of the Athenian empire (and so 'colonialist propaganda), or if it was really about the threat and danger of immigrants to Athens. Because audiences aren't monolithic, I think it probably can legitimately be interpreted as all three, depending on who is in your audience.

I've been trying to think of the play within the context of Athens' descent in the 460s and 450s into anti-immigrant policies and strict monitoring of citizenship. The play was performed around 463 BCE, around the time that the new category of 'metic' (translated as 'immigrant' or 'resident foreigner') was created and only a decade before Athens began racializing its citizenship with the passage of the law requiring double Athenian parentage for citizenship and emphasizing its autochthonous birth.

In the play, the king initially rejects the supplication of the Danaids. And he does so based on reasons we all may find familiar--that the Danaids aren't really in danger at home (387-91) or, more importantly:

Wow. Hmmmm. I've clearly been feeling a bit cynical given the anti-immigrant, anti-refugee world we seem to have devolved into in recent years.

My point being, however, that the protestors of the Sorbonne production have every right to see the #blackface in this play as racist. They have every right to worry that the play is not being produced thoughtfully or with a message of empathy in mind. Maybe, with his costumes and #blackface, the director was trying to invoke the Ovadia Sicily production. But he failed to understand that France is not Sicily and protestors are well within their rights to sense that a poorly staged, colonialist version of this play could do more to engender prejudice than discourage it. And the director and performers should know better than to don #blackface in rehearsal or performance and then cry foul when they get called on it.

Here's a picture of the performance (possibly last year's?). See if you can tell me why they might think something was awry:

Since the protestors blocked the performance, there have been a series of statements from the uni and the director with excuses replete with condemnations of the protestors. John Ma sums it up on a Twitter discussion about it:

The most recent responses have the director saying that it was intended that the actors would wear masks (according to ancient Greek tradition) for the performance, not #blackface. And yet:

Because, one of the remarkable things about the play is that, although the Danaids explicitly refer to themselves as "black" ('black, sun-beaten people" μελανθὲς ἡλιόκτυπον γένος lines 154-5), it is not considered an important mark of their difference at all when they arrive in Greece from Egypt. When the Argive king Pelasgos first sees them, he thinks they look very foreign, but doesn't even notice their skin color:

This group that we address is unhellenic, luxuriating in barbarian finery and delicate cloth. What country do they come from? The women of Argos, indeed of all Greek lands, do not wear such clothes. It is astonishing that you dare to travel to this land, fearlessly, without heralds, without sponsors, without guides. And yet here are the branches of suppliants, laid out according to custom next to you in front of the assembled gods. This alone would assert your Greekness…(ll 245-54).This play is one of many indicators from ancient Greece that skin color was not usually associated with prejudice. And yet this director managed to take this play and make it all about skin color and prejudice through the employing of a well known racist practice of #blackface--which, by the way, has a long tradition of being just as racist in France as it does in the US.

Additional irony? The thing that marks them as foreign in Aeschylus is their clothing. See anything in the pictures about their clothes? Yep--Greek-style. This director has reversed Aeschylus.

Of course, there is much else to be discussed concerning the reaction to the play. The protestors are reacting to the #blackface and placing it within the context of France's history of colonialism (and its 'official' state denial of racism as a phenomenon in France):

Over the last two weeks, I've given a series of talks on Aeschylus' play and asked myself the question of whether in its original context it was a play about welcoming refugees or about the benefits of the Athenian empire (and so 'colonialist propaganda), or if it was really about the threat and danger of immigrants to Athens. Because audiences aren't monolithic, I think it probably can legitimately be interpreted as all three, depending on who is in your audience.

I've been trying to think of the play within the context of Athens' descent in the 460s and 450s into anti-immigrant policies and strict monitoring of citizenship. The play was performed around 463 BCE, around the time that the new category of 'metic' (translated as 'immigrant' or 'resident foreigner') was created and only a decade before Athens began racializing its citizenship with the passage of the law requiring double Athenian parentage for citizenship and emphasizing its autochthonous birth.

In the play, the king initially rejects the supplication of the Danaids. And he does so based on reasons we all may find familiar--that the Danaids aren't really in danger at home (387-91) or, more importantly:

The case is not easy to judge: don’t choose me to judge it. I have already said I am not prepared to do this without the people’s approval, even though I have the power--if something rather bad should happen the people may end up saying “By giving privileges to foreigners you destroyed our city” (397-401).And when he is finally convinced to take their petition to the assembly and it is approved and the Danaids enter the city? They bring a war to the city (the sons of Aegyptus invade!), the Argives lose, Pelasgos dies, and, by the end of the last play in the trilogy (our extant play is only the first in a three-play series), the city is under the foreign rule of one Aegyptids (Lynceus) and his wife, the only Danaid (Hypermnestra) who didn't kill her husband on his wedding night. So much for welcoming in refugees as a benefit to the city...

Wow. Hmmmm. I've clearly been feeling a bit cynical given the anti-immigrant, anti-refugee world we seem to have devolved into in recent years.

My point being, however, that the protestors of the Sorbonne production have every right to see the #blackface in this play as racist. They have every right to worry that the play is not being produced thoughtfully or with a message of empathy in mind. Maybe, with his costumes and #blackface, the director was trying to invoke the Ovadia Sicily production. But he failed to understand that France is not Sicily and protestors are well within their rights to sense that a poorly staged, colonialist version of this play could do more to engender prejudice than discourage it. And the director and performers should know better than to don #blackface in rehearsal or performance and then cry foul when they get called on it.